Text Size:

Current Size: 100%

RIGHT-mouse-click the "Download.." link below, and in the drop-down menu that appears, if you use FireFox select "Save Link As..."; or if you use Internet Explorer select "Save Target As...".

Download http://www.great-grandma.com/aquakeys/files/pet/aud/pet-ch_06.mp3

http://www.great-grandma.com/aquakeys/files/pet/aud/pet-ch_06.mp3

See the bottom of this book's cover page here.

Frequently when parents learn Active Listening in our classes, a parent becomes impatient and asks, "When do we learn how to get the kids to listen to us? That's the problem in our home."

Undoubtedly that is the problem in many homes, for children inevitably annoy, disturb, and frustrate parents at times; they can be thoughtless and inconsiderate as they go about trying to meet their own needs. Like small puppies, kids can be boisterous and destructive, noisy and demanding. As every parent knows, children can cause extra work, delay you when you are in a hurry, pester you when you are tired, talk when you want quiet, make huge messes, neglect their chores, call you names, stay out too late, and so on ad infinitum.

Mothers arid fathers need effective ways to deal with children's behavior that interferes with the parents' needs.

After all, parents do have needs. They have their own lives to live, and the right to derive enjoyment and satisfaction from their existence. Yet, many parents have allowed their children to be in a favored position in the family. These children demand that their needs are met but they are inconsiderate of the needs of their parents.

Much to their regret, many parents find that as their children get older, they act as if they are oblivious to their parents' needs. When parents permit this to happen, their children move through life as if it is a one-way street for the continuous gratification of their own needs. Parents of such children usually become embittered, and feel strong resentment toward their "ungrateful," "selfish" kids.

When Mrs. Lloyd enrolled in P.E.T., she was puzzled and hurt because her daughter, Brianna, was becoming more and more selfish and inconsiderate. Indulged by both parents since infancy, Brianna contributed very little to the family, yet expected her parents to do everything she requested. If she did not get her way, she would say abusive things about her parents, throw tantrums, or walk out of the house and not return for hours.

Mrs. Lloyd, raised by her own mother to think of conflict or strong feelings as something "good" families are not supposed to let out, gave in to most of Brianna's de mands in order to avoid a scene or as she put it, "to keep peace and tranquility in the family." As Brianna moved into adolescence, she became even more arrogant and selfcentered, seldom helping around the house and rarely making adjustments out of consideration for the needs of her parents.

Often she told her parents that it was their responsibility that she was brought into the world and therefore their duty to take care of her needs. Mrs. Lloyd, a conscientious parent who wanted desperately to be a good mother, was beginning to develop deep feelings of resentment toward Brianna. After all she had done for Brianna, it hurt and angered her to see Brianna's selfishness and lack of consideration for the needs of the parents.

"We do all the giving, she does all the taking," was the way this mother described the family situation.

Mrs. Lloyd was certain she was doing something wrong, but she did not dream that Brianna's behavior was the direct result of the mother's fear of standing up for her own rights. P.E.T. first helped her accept the legitimacy of her own needs and then gave her specific skills for confronting Brianna when her behavior was unacceptable to her parents.

What can parents do when they cannot genuinely accept a child's behavior? How can they get the child to consider the parents' needs? Now we will focus on how parents can talk to kids so they will listen to their feelings and be considerate of their needs.

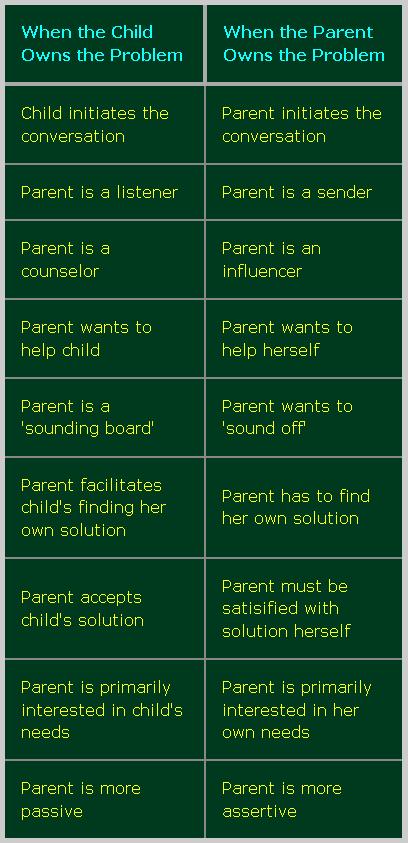

Entirely different communication skills are required when the child causes the parent a problem as opposed to those needed when the child causes herself a problem. In the latter case, the child "owns" the problem; when the child causes the parent a problem, the parent "owns" it. This chapter will show parents what skills they need for effectiveness in solving problems that their children cause them.

Many parents initially have difficulty understanding the concept of ownership of problems. Perhaps they are too accustomed to think in terms of having "problem children," which locates the problem within the child, rather than the parent. It is critical that parents understand the difference. The best clue for parents comes when they begin to sense their own inner feelings of unacceptance, when they begin to have inner feelings of annoyance, frustration, resentment. They may find themselves becoming tense, experiencing discomfort, not liking what the child is doing, or monitoring her behavior.

Suppose:

All these behaviors actually or potentially threaten legitimate needs of parents. The child's behavior in some tangible or direct way affects the parent: Mother does not want her dinner wasted, her rug soiled, her discussion interrupted, and so on.

Confronted with such behaviors as these, a parent needs ways to help herself, not the child. The following chart helps to show the difference between the parent's role when she owns the problem, and when the child does.

Parents have several alternatives when they own the problem:

Mr. Adams' son, Jimmy, takes his father's tools out of the toolbox and usually leaves them scattered over the yard. This is unacceptable to Mr. Adams, so he owns this problem.

He can confront Jimmy, say something, hoping this might modify Jimmy's behavior.

He can modify Jimmy's environment by buying him his own set of junior tools, hoping this will modify Jimmy's behavior.

He can try to modify his own attitudes about Jimmy's behavior, saying to himself that "boys will be boys" or "he'll learn proper care of tools in time."

In this chapter, we shall deal only with the first alternative, focusing on how parents can talk or confront their kids in order to modify behavior that is unacceptable to the parents. Referring to the Behavior Window, our focus will now be on the bottom part- when the parent owns the problem. In later chapters, we will deal with the other two alternatives.

It is no exaggeration that ninety-nine out of a hundred parents in our classes use ineffective methods of communicating when their children's behavior is interfering with the parents' lives. In a class the instructor reads aloud a typical family situation of a child upsetting his parent:

Then the instructor asks everybody to write on a sheet of paper exactly what each would say to the child in this situation. (The reader may participate in this exercise by writing down his or her verbal response).

Then the instructor reads another situation and then a third, and asks everyone to write his or her responses.

We discover from this classroom experiment that parents, with rare exceptions, handle these rather typical situations ineffectively. They say things to the child that have a high probability of:

Parents are shocked at these findings, because it is a rare parent who consciously intends to do these things to her child. Most parents simply have never thought about the effects their words can produce on their children.

In our classes we then describe each of these ineffective ways of verbally confronting children and point out in greater detail why they are ineffective.

Have you ever been just about ready to do something considerate for a person (or initiate some change in your behavior to meet a person's needs) when all of a sudden that person directs you, exhorts you, or advises you to do exactly what you were going to do on your own?

Your reaction was probably, "I didn't need to be told" or "If you had waited a minute, I would have done that without being told." Or you probably got irritated because you felt that the other person did not trust you enough or took away the chance for you to do something considerate for her on your own initiative.

When people do this to you, they are "sending a solution." This is precisely what parents often do with children. They do not wait for the child to initiate considerate behav ior; they tell her what she must or should or ought to do. All the following types of messages "send a solution":

1. ORDERING, DIRECTING, COMMANDING

2. WARNING, ADMONISHING, THREATENING

3. EXHORTING, PREACHING, MORALIZING

4. ADVISING, GIVING SUGGESTIONS OR SOLUTIONS

These kinds of verbal responses communicate to the child your solution for her- precisely what you think she must do. You call the shots; you are in control; you are taking over; you are cracking the whip. You are leaving her out of it. The first type of message orders her to employ your solution; the second threatens her; the third exhorts her; the fourth advises her.

Parents ask, "What's so wrong with sending your solution- after all, isn't she causing me a problem?" True, she is. But giving her the solution to your problem can have these effects:

If a friend is visiting in your home and happens to put his feet on the cushions of one of your new dining room chairs, you certainly would not say to him:

This sounds ridiculous in a situation involving a friend because most people treat friends with more respect: Adults want their friends to "save face." They also assume that a friend has brains enough to find his own solution to your problem once he is told what the problem is. An adult would simply tell the friend her feelings. She would leave it up to him to respond appropriately and assume he would be considerate enough to respect her feelings. Most likely the chair owner would send some such messages as:

These messages do not "send a solution." People generally send this type of message to friends but seldom to their own children; they naturally refrain from ordering, exhorting, threatening, and advising friends to modify their behavior in some particular way, yet as parents they do this every day with their children.

No wonder children resist or respond with defensiveness and hostility. No wonder children feel put-down, squelched, controlled. No wonder they "lose face." No wonder some grow up submissively expecting to be handed solutions by everyone. Parents frequently complain that their children are not responsible in the family; they do not show consideration for the needs of parents. How are children ever going to learn responsibility when parents take away every chance for the child to do something responsible on her own out of consideration for her parents' needs?

Everyone knows what it feels like to be "put down" by a message that communicates blame, judgment, ridicule, criticism, or shame. In confronting children, parents rely heavily on such messages. "Put-down messages" may fall into any of these categories:

1. JUDGING, CRITICIZING, BLAMING

2. NAME-CALLING, RIDICULING, SHAMING

3. INTERPRETING, DIAGNOSING, PSYCHOANALYZING

4. TEACHING, INSTRUCTING

All these are put-downs- they impugn the child's character, deprecate her as a person, shatter her self-esteem, underline her inadequacies, cast a judgment on her personality. They point the finger of blame toward the child.

What effects are these messages likely to produce?

Put-down messages can have devastating effects on a child's developing self-concept. The child who is bombarded with messages that deprecate her will learn to look at herself as no good, bad, worthless, lazy, thoughtless, inconsiderate, "dumb," inadequate, unacceptable, and so on. Because a poor self-concept formed in childhood has a tendency to persist into adulthood, put-down messages sow the seeds for handicapping a person throughout her lifetime.

These are the ways that parents, day after day, contribute to the destruction of their children's ego or self-esteem. Like drops of water falling on a rock, these daily messages gradually, imperceptibly leave a destructive effect on children.

Parents' talk can also build. Most parents, once they become aware of the destructive power of put-down messages are eager to learn more effective ways of confronting children. In our classes we never encountered a parent who consciously wanted to destroy her child's self-esteem.

An easy way for parents to see the difference between ineffective and effective confrontation is to think of sending either You-Messages or I-Messages. When we ask parents to examine the previously noted ineffective messages, they are surprised to discover that almost all begin with the word "You" or contain that word. All these messages are "You"-oriented:

But when a parent simply tells a child how some unacceptable behavior is making the parent feel, the message generally turns out to be an I-Message.

Parents readily understand the difference between I-Messages and You-Messages, but its full significance is appreciated only after we return to the diagram of the communication process, first introduced to explain Active Listening. It helps parents appreciate the importance of I-Messages.

When a child's behavior is unacceptable to a parent because in some tangible way it interferes with the parent's enjoyment of life or her right to satisfy her own needs, the parent clearly "owns" the problem. She is upset, disappointed, tired, worried, harassed, burdened, etc., and to let the child know what is inside her, the parent must select a suitable code. For the parent who is tired and does not feel like playing with her five-year-old child, our diagram would look like this:

But if this parent selects a code that is "you"-oriented, she would not be coding her "feeling tired" accurately:

"You are being a pest" is a very poor code for the parent's tired feeling. A code that is clear and accurate would always be an I-Message: "I am tired," "I don't feel up to playing," "I want to rest."

This communicates the feeling the parent is experiencing. A You-Message code does not send the feeling. It refers much more to the child than to the parent. A You-Message is child-oriented, not parent-oriented.

Consider these messages from the point of view of what the child hears:

The first message is decoded by the child as an evaluation of her. The second is decoded as a statement of fact about the parent. You-Messages are poor codes for communicating what a parent is feeling, because they will most often be decoded by the child in terms of either what she should do (sending a solution) or how bad she is (sending blame or evaluation).

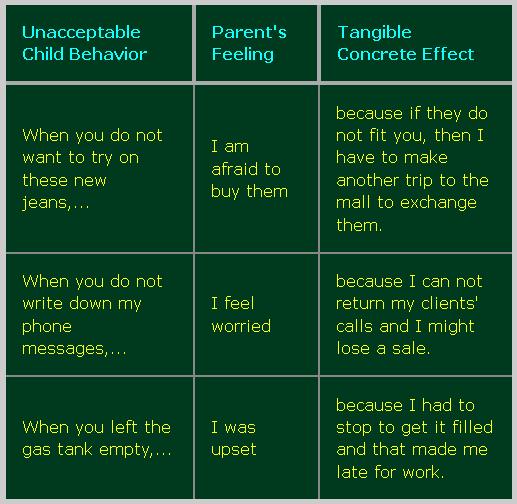

Children will be much more likely to change their unacceptable behavior if their parents send I-Messages containing these three parts:

[BEHAVIOR + FEELING + EFFECT.]

Behavior is something that the child does or says. This part of the I-Message is a simple description of the child's unacceptable behavior; what she's doing that bothers you, not your label or judgment of that behavior.

Here's an example of a child who left for school saying that she would be home right after school got out. She came home an hour later without calling.

The key here is to remember to describe the behavior, not judge it.

Non-Blameful Description of the Child's Behavior: "When you didn't come home from school on time, and you didn't call to say you'd be late,..."

Judgement or Label: "It was inconsiderate of you not to call."

When parents send You-Messages, they needn't identify how they feel as a consequence of a child's unacceptable behavior. It's just a matter of blurting out a command, threat, a put-down: "You're driving me crazy," "You're lazy," etc. Not so when parents try to send an I-Message. Now they need to know how they feel. "Am I angry or afraid or worried or embarrassed or just what?"

When parents begin to send I-Messages, not only do they notice changes in their children but they also experience a significant change in themselves. The different words I've heard used all seem to mean greater honesty:

Apparently the old idea, "You become what you do," applies here, too. By using a new form of communication, parents begin to feel inside themselves the very honesty their I-Messages communicate to others. The I-Message skill provides parents with the vehicle for getting in touch with their real feelings. (I'll say more about feelings in the next chapter.)

When I-Messages fail to influence a child to modify behavior that is causing the parent a problem, it is sometimes because the parent has sent one or more incomplete I-Messages. Often, the two-part I-Message (a description of the unacceptable behavior and the parent's feeling about it) will be enough to get the child to change.

But an effective I-Message often needs to contain a third part- kids need to know why their behavior is a problem. So it's important to tell them the tangible and concrete effect that their behavior is having on you.

Most often, a tangible and concrete effect is something that costs you money, time, extra work or inconvenience. It might prevent you from doing something you want or need to do. It might physically hurt you, make you tired, or cause you pain or discomfort.

When you send a complete three-part I-Message, you tell the child the whole story- not only what she is doing that is giving you a problem, but also what feeling you have about it, and equally important, why the behavior will cause or has caused you a problem.

Here are some examples:

Remember, the whole purpose of sending I-Messages is to influence children to change whatever they are doing at the time. Usually it's not enough to describe the behavior you find unacceptable and tell them you're upset about it- or angry or frustrated. They need to know why.

Put yourself in your child's shoes. You're doing something to get some need of yours met (or to avoid something that's unpleasant to you). Now just because you say, in effect, "I'm upset with what you're doing" are you motivated to change your behavior? Probably not. Because you have to hear a very good reason to change.

This is why parents need to be very explicit about the tangible and concrete effect of a child's behavior on them. Failure to communicate this to the child leaves her with no good reason to change.

In addition to giving children a specific reason why the parent finds their behavior unacceptable, thereby increasing the chances they will be motivate to change, the complete three-part I-Message has a significant effect on the parents. We discovered that when parents try to communicate the "tangible effect" portion of the I-Message, they often realize there is no tangible effect at all. A mother explained this phenomenon.

"I found I-Messages most valuable in helping me see how arbitrary I am with my kids. When I try to send all three parts and I get to the part that explains what effect the behavior has on me, it would make me think, 'Well, I have no good reason!' If I say, 'I can't stand it when you're making so much noise around the house,' when I got to the 'because; I'd ask myself, 'Why am I annoyed by it?' and realized I'm really not annoyed. So I've gotten into the habit now that if I can't think of any effect it has on me, I just say to the kid, 'Forget I ever said anything; because it seemed so arbitrary.... It's neat, you know, discovering that I couldn't even find a reason about half the time."

The clue to why this mother felt her discovery was "neat" was revealed when she later explained:

Thirty years ago, I would not have predicted that by teaching parents to send a complete three-part I-Message, we would be helping them discover they didn't even need to send an I-Message. By convincing parents they should explain to their kids why they found a particular behavior unacceptable, we inadvertently gave them a method that in many cases made the unacceptable behavior acceptable.

I-Messages are more effective in influencing a child to modify behavior that is unacceptable to the parent as well as healthier for the child and the parent-child relationship.

The I-Message is much less apt to provoke resistance and rebellion. To communicate to a child honestly the effect of her behavior on you is far less threatening than to suggest that there is something bad about her because she engaged in that behavior. Think of the significant difference in a child's reaction to these two messages, sent by a parent after a child kicks her in the shins:

The first message only tells the child how her kick made you feel, a fact with which she can hardly argue. The second tells the child that she was "bad" and warns her not to do it again, both of which she can argue against and probably resist strongly.

I-Messages are also infinitely more effective because they place responsibility within the child for modifying her behavior. "Ouch! That really hurt me" and "I don't like to be kicked" tell the child how you feel, yet leave her to be responsible for doing something about it.

Consequently, I-Messages help a child grow, help her learn to assume responsibility for her own behavior. An I-Message tells a child that you are leaving the responsibility with her, trusting her to handle the situation constructively, trusting her to respect your needs, giving her a chance to start behaving constructively.

Because I-Messages are honest, they tend to influence children to send similar honest messages whenever they have a feeling. I-Messages from one person in a relationship promote I-Messages from the other. This is why, in deteriorating relationships, conflicts often degenerate into mutual name-calling and reciprocal blaming:

PARENT: You're getting awfully irresponsible about doing your dishes after breakfast. [You-Message.]

CHILD: You don't always do yours every morning. [You-Message.]

PARENT: That's different- I have lots of other things to do around the house, picking up after a bunch of messy children. [You-Message.]

CHILD: I haven't been messy. [Defensive message.]

PARENT: You're just as bad as the others, and you know it. [You-Message.]

CHILD: You expect everyone to be perfect. [You-Message.]

PARENT: Well, you certainly have a long way to go to reach that when it comes to picking up. [You-Message.]

CHILD: You're so picky about the house. [You-Message.]

This is typical of many conversations between parents and children when the parent starts her confrontation with a You-Message. Invariably, they end up in a struggle, with both alternately defending and attacking.

I-Messages are much less likely to produce such a struggle. This is not to say that if parents send I-Messages everything will be sweetness and light. Understandably, children do not like to hear that their behavior has caused a problem for their parents (just like adults, who are never exactly comfortable when someone confronts them with the fact that their behavior has caused pain). Nevertheless, telling someone how you feel is far less threatening than accusing her of causing a bad feeling.

It takes a certain amount of courage to send I-Messages, but the rewards are generally well worth the risks. It takes courage and inner security for a person to ex pose her inner feelings in a relationship. The sender of an honest I-Message risks becoming known to the other as she really is. She is opening herself up being "transparently real," revealing her "human-ness." She tells the other that she is a person capable of being hurt or embarrassed or frightened or disappointed or angry or discouraged, and so on.

For a person to reveal how she feels means opening herself to be viewed by the other. What will the other person think of me? Will I be re' c ed? Will the other person think less of me? Parents, particularly, find it difficult to be transparently real with children because they like to be seen as infallible- without weaknesses, vulnerabilities, inadequacies. For many parents, it is much easier to hide their feelings under a You-Message that puts the blame on the child than to expose their own human-ness.

Probably the greatest reward that comes to a parent from being transparent is the relationship it promotes with the child. Honesty and openness foster intimacy- a truly interpersonal relationship. My child gets to know me as I am, which then encourages her to reveal to me who she is. Instead of being alienated from each other, we develop a relationship of closeness. Ours becomes an authentic relationship- two real persons, willing to be known in our realness to each other.

When parents and children learn to be open and honest with each other, they no longer are "strangers in the same house." The parents can have the joy of being parents to a real person- and the children are blessed by having real persons as parents.