Text Size:

Current Size: 100%

RIGHT-mouse-click the "Download.." link below, and in the drop-down menu that appears, if you use FireFox select "Save Link As..."; or if you use Internet Explorer select "Save Target As...".

Download http://www.great-grandma.com/aquakeys/files/pet/aud/pet-ch_13.mp3

http://www.great-grandma.com/aquakeys/files/pet/aud/pet-ch_13.mp3

See the bottom of this book's cover page here.

Even after parents in P.E.T. become convinced they want to begin using the no-lose method, they pose questions about how to get started. Also, some parents run into difficulties when they first begin. Here are some pointers on getting started, on handling some of the most common problems parents encounter, and on resolving irritating conflicts that develop between children.

Parents who have had the most success getting started with the no-lose method take seriously our advice to sit down with their kids and explain what the method is all about. Remember, most kids are as unfamiliar with this method as the parents. Accustomed to having conflicts with parents resolved by Method 1 or Method 2, they need to be told how Method 3 differs.

Parents explain all three methods and describe the differences. They admit that often they have won at the expense of the kids losing, and vice versa. Then they freely express their eagerness to get away from the win-lose methods and try the no-lose method.

Kids usually get turned on by such an introduction. They are curious to learn about Method 3 and are anxious to try it. Some parents first explain that they have been taking a course in how to be more effective parents and that this new method is one of the things they would now like to try out. Of course, this approach is not appropriate for youngsters under three. With them, you just start out with no explanation.

It has been helpful for parents to understand that the no-lose method really involves six separate steps. When parents follow these steps, they are much more likely to have successful experiences:

There are some key points to be understood about each of these six steps. When parents understand and apply these key points, they avoid many difficulties and pitfalls. Even though some "quickie" conflicts get worked out without going through all the steps, parents do better when they understand what is involved at each stage.

This is the critical phase when parents want the child to become involved. They have to get his attention and then secure his willingness to enter into problem-solving. Their chances of doing this are much greater if they remember to:

Step 1 is the most critical step in Method 3 because this is when the needs of both the parents and the children get defined. So often what appears to be a problem or conflict turns out to be a "presenting problem," and not the real one.

Further, parents unconsciously come in with preconceived solutions that will meet their need rather than express the need itself. Separating needs from solutions can be very difficult because even when people use the word need, what they are saying is often a solution that would meet a need.

While Active Listening is the most important skill to use in separating needs from solutions, the questions "What will that do for me?" or "What will that do for you?" can also be extremely helpful. For example, if you say, "I need a new car," is that a need or a solution? Ask the question "What will that do for me?" Possible answers might be: I'll get to work safely," "I'll feel good about my image/myself," "I'll save money since my old car uses too much gas and requires lots of repairs." These answers are the needs; a new car is the solution.

Your child might say, "I need my own room," which is really a solution. What will having his own room do for the child? It would provide privacy, or a feeling of having his own space or quiet, etc. These are the underlying needs; a room of his own is the solution.

If the underlying needs of both the parent and the child are not clearly understood and expressed, the process will bog down. The subsequent steps will be misdirected and the conflict won't be resolved.

In this phase, the key is to generate a variety of solutions. The parent can suggest: "What are some of the things we might do?" "Let's think of possible solutions," "Let's put our heads to work and come up with some possible solutions," "There must be a lot of different ways we can solve this problem." These additional key points will help:

In this phase, it is legitimate to start evaluating the various solutions. The parent may say, "All right, which of these solutions look best?" or "Now, let's see which solution we feel is the one we want" or "What do we think of these various solutions we have come up with?" or "Are any of these better than the others?"

Generally, the solutions get narrowed down to one or two that seem best by eliminating those that are not acceptable to either parent or the kids (for whatever reason). At this stage parents must remember to be honest in stating their own feelings- "I wouldn't be happy with that," or "That wouldn't meet my need," or "I don't think that one would seem fair to me."

This step is not as difficult to work through as parents often think. When the other steps have been followed and the exchange of ideas and reactions has been open and hon est, a clearly superior solution often emerges naturally from the discussion. Sometimes either the parent or a child has suggested a very creative solution that obviously is the best one- and is also acceptable to everyone.

Some tips for arriving at a final decision are:

Frequently, after a decision is reached there is a need to spell out in some detail exactly how the decision will be implemented. Parents and kids may need to address them selves to "Who is to do what, by when?" or "Now what do we need to do to carry this out?" or "When do we start?"

In conflicts about chores and work duties, for example, "How often?" "On what days?" and "What are to be the standards of performance required?" are questions that often must be discussed.

In conflicts about bedtime, a family may want to discuss who is going to watch the clock and call time.

In conflicts about the neatness of the children's rooms, the issue of "how neat" may have to be explored.

Sometimes decisions may require purchases, such as a board for a message center, a clothes hamper, a second phone line, another TV set, a hair dryer, and so on. In such cases it may be necessary to determine who is to shop for these, or even who is to pay for them.

Questions of implementation are best delayed until after there is a clear agreement on the final decision. Our experience is that once the final decision has been reached, the implementation issues are usually worked out rather easily.

Not all initial decisions from the no-lose method turn out to be good ones. Consequently, parents sometimes need to check back with a child to ask if he is still happy with the decision. Kids often commit themselves to a decision that later proves difficult to carry out. Or a parent may find it difficult to keep his bargain, for a variety of reasons. Parents may want to check back after a while with, "How is our decision working out?" "Are you still satisfied with our decision?" This communicates to kids your concern about their needs.

Sometimes the follow-up turns up information that requires the initial decision to be modified. Taking out the trash once every day might turn out to be impossible or unnecessary. Or, coming in at 11:00 P.M. on weekend nights proves to be impossible when the kids go to a movie in the next town. One family discovered that their no-lose resolution of the chore problem required their daughter, who agreed to do the evening dishes, to work an average of five to six hours a week, while their son, whose job it was to do a weekly cleanup of their common bathroom and family room, needed to work only about three hours a week. This seemed unfair to the daughter, so the decision was modified after a couple of weeks' trial.

Of course, not all no-lose conflict-resolution sessions proceed in an orderly fashion through all six steps. Sometimes conflicts are resolved after only one solution has been proposed. Sometimes the final solution pops out of someone's mouth during Step 3, when they are evaluating previously proposed solutions. Nevertheless, it pays to keep the six steps in mind.

Because the no-lose method requires the involved parties to join together in problem-solving, effective communication is a prerequisite. Consequently, parents must do a great deal of Active Listening, and must send clear I-Messages. Parents who have not learned these skills seldom have success with the no-lose method.

Active Listening is required, first, because parents need to understand the feelings or needs of the kids. What do they want? Why do they persist in wanting to do something even after they know it is not acceptable to their parents? What needs are causing them to behave in a certain way?

Why is Bonnie resisting going to nursery school? Why does Jane not want to wear the "ugly" coat? Why does Nathan cry and fight his mother when she drops him off at the baby-sitter's? What are my daughter's needs that make it so important for her to go to the beach during the Easter vacation?

Active Listening is a potent tool for helping a youngster to open up and reveal his real needs and true feelings. When these become understood by the parent, it is often an easy next step to think of another way of meeting those needs that will not involve behavior unacceptable to the parent.

Since strong feelings may come out during problem-solving- from parents as well as youngsters, Active Listening is critically important in helping to release feelings and dissipate them, so that effective problem-solving can continue.

Finally, Active Listening is an important way to let kids know that their proposed solutions are understood and accepted as proposals made in good faith; and that their thoughts and evaluations concerning all proposed solutions are wanted and accepted.

I-Messages are critical in the no-lose process so kids will know how the parent feels, without impugning the character of the child or putting him down with blame and shame. You-Messages in conflict-resolution usually provoke counter You-Messages and cause the discussion to degenerate into a nonproductive verbal battle with the contestants vying to see who can best clobber the other with insults.

I-Messages also must be used to let kids know that parents have needs and are serious about seeing that those needs are not going to be ignored just because the youngster has his needs. I-Messages communicate the parent's own limits- what he cannot tolerate and what he does not want to sacrifice. I-Messages convey, "I am a person with needs and feelings," "I have a right to enjoy life," "I have rights in our home."

Parents in P.E.T. are advised that their first no-lose problem-solving session probably should take up some long-standing conflicts rather than a more immediate and incendiary one. It is also wise at this first session to give kids a chance to identify some problems that are bothering them. Thus, a first attempt at no-lose conflict-resolution might be presented by a parent in some such fashion as this:

The advantages of starting with problems identified by the kids are rather obvious. First, kids are delighted to see that this new method can work to their benefit. Second, it keeps them from the incorrect notion that their parents have picked up some new device to get just their own needs met. One family that started out this way ended up with a list of grievances against their parents' behavior:

After they got their grievances listed, these teenagers were much more receptive to hearing some of the problems Mom or Dad was having with their behavior.

Sometimes it is wise for a family to start out by talking about the ground rules they might need to conduct an effective no-lose conflict-resolution session. Parents might suggest that all agree to let one person talk without being interrupted. It should be clearly stated that voting is not to be used- you are after a solution acceptable to everyone. Agree to go out of the room when two people are resolving a conflict not involving the others. Agree on no physical horseplay during the problem-solving. One family even agreed that during their problem-solving conferences they would not answer the telephone. Many families have found it very useful to use a white board or a pad of paper to assist with complex problems.

Parents often make mistakes trying to put the new method to work and it also takes time for kids to learn how to resolve conflicts without power, especially adolescents who have had years of experience with win-lose methods. Both parents and their offspring have to undo some old patterns of behavior and learn some new ones, and this naturally doesn't always work without a hitch. From parents in our P.E.T. classes we have learned what mistakes are most frequently made and what the common problems are.

Some parents encounter resistance to the no-lose method- invariably when the kids are teenagers accustomed to years of continuous power struggle with parents. They report:

The best way to handle such distrust and resistance is for the parents temporarily to put aside the problem-solving and try to understand with empathy what the child is really saying. Active Listening is the best tool for finding out. It may encourage kids to express more of their feelings. If they do, that is progress because, after their feelings get ventilated, these youngsters will often enter into problem-solving. If they remain withdrawn and unwilling to participate, parents will want to send their own feelings- as I-Messages, of course:

Usually these messages are effective in dispelling distrust and resistance. If not, parents can simply leave the problem unresolved for a day or two and try the no-lose method again.

We tell parents, "Just remember how skeptical and distrustful you were when you heard us talk about the no-lose method the first time in class. That may help you understand your kids' first skeptical reactions."

This is one of the most frequent fears of parents. While it is justifiable in some cases, surprisingly few no-lose conflict-resolution sessions fail to come up with an acceptable solution. When a family encounters such a stalemate or deadlock, it is usually because parents and children are still in a win-lose, power-struggle frame of mind.

Our advice to parents is: try everything you can think of in such cases. For instance:

Usually, one or several of these approaches works and problem-solving gets started again.

"We tried the no-lose method and got nowhere. So I had to put my foot down and make the decision."

Some parents are tempted to revert to Method 1. Usually this has rather severe consequences. The kids are angry; they feel they were duped into believing that their parents were trying a new method; and the next time the no-lose method is tried they will be even more distrustful and disbelieving.

Parents are strongly urged to avoid reverting to Method 1. Also, it is just as disastrous to revert to Method 2 and let the kids win, for the next time the no-lose method is tried, they will be primed to keep fighting until they again get their own way.

Parents have reported that they (or the kids) found themselves, after a no-lose decision had been reached, building into the agreement the penalties or punishments to be administered if the kids did not keep to their agreement.

My earlier reaction to these reports was to suggest that mutually set penalties and punishments might be all right, if they also applied to the parents, should they not uphold their end of the bargain. I now think differently about this issue.

It is far better for parents to avoid bringing up penal- ties or punishments for failure to stick to an agreement or carry out a Method 3 decision.

In the first place, parents will want to communicate to the youngsters that punishment is not to be used at all any more, even if it is suggested by the kids, as it often will be.

Secondly, more is gained by an attitude of trust- trust in the kids' good intentions and integrity. Youngsters tell us, "When I feel trusted, I am less likely to betray that trust. But when I feel my parent or a teacher is not trusting me, I might as well go ahead and do what they already think I've done. I'm already bad in their opinion. I've already lost, so why not go and do it anyway."

In the no-lose method, parents should simply assume that the kids will carry out the decision. That is part of the new method- trust in each other, trust in keeping to commitments; sticking to promises, holding up one's end of the bargain. Any talk about penalties and punishments is bound to communicate distrust, doubt, suspicion, pessimism. This is not to say that kids will always stick to their agreement. They won't. It says merely that parents should assume that they will. "Innocent until proven guilty" or "responsible until proven irresponsible" is the philosophy we recommend.

It is almost inevitable that kids sometimes will not keep their commitment. Here are some of the reasons:

Our parents have reported all of these reasons for kids failing to keep to their commitments.

We teach parents to confront, directly and honestly, any youngster who has not stuck to an agreement. The key is to send the child an I-Message- no blame, no put-down, no threat. Also the confrontation should come as soon as possible, perhaps like this:

Such I-Messages will invoke some response from the youngster that may give you more information and help you to understand the reason. Again this is a time to listen actively. But always, in the end, the parent must make it clear that in the no-lose method each person is expected to be self-responsible and trustworthy. The commitments are expected to be met: "This is no game we're playing- we're seriously trying to consider the needs of one another."

That may take real discipline, real integrity, real work. Depending on the reasons why a child did not keep his word, parents may (1) find the I-Messages are effective; (2) find they need to reopen the problem and find a better solution; or (3) want to help the child look for ways to help him remember.

If a youngster forgets, parents can raise the problem of what he might do to remember the next time. Does he need a clock, a timer, a note to himself, a message on the bulletin board, a string around his finger, a calendar, a sign in his room?

Should the parents remind the youngster? Should they take on the responsibility of telling him when he is to do what he agreed to do? In P.E.T. we say definitely not. Apart from the inconvenience to the parent, it has the effect of keeping the child dependent, slowing down the development of his self-discipline and self-responsibility. Reminding children to do what they committed themselves to do is coddling them- it treats them as if they are immature and irresponsible. And that is what they will continue to be, unless parents start right away to shift the seat of responsibility to the child, where it belongs. Then, if the child slips, send him an I-Message.

Frequently parents who have relied heavily on Method 2 report difficulties in switching over to Method 3 because their children, accustomed to getting their way most of the time, strongly resist becoming involved in a problem-solving method that might require them to give a little, cooperate, or compromise. Such children are so used to winning at the expense of their parents that they are naturally reluctant to give up this advantageous competitive position. In such families, when the parents initially encounter strong resistance to the no-lose method, they sometimes get scared off and give up trying to make it work. Often they are parents who gravitated to Method 2 because of fear of their children's anger or tears.

A change to Method 3 for previously permissive parents will therefore require of them much more strength and firmness than they have been accustomed to exhibiting with their children. These parents need somehow to find a new source of strength in order to move away from their previous "peace at any price" posture. It often helps to remind them of the terrible price they will have to pay in the future if their kids always win. They have to be convinced that they as parents have rights, too. Or they must be reminded that their usual giving in to the child has made him selfish and inconsiderate. Parents like this need some convincing that parenthood can be a joy when their needs are met, too. They must want to change, and they must be prepared to get a lot of static from the child when they change over to Method 3. During the period of changing over, the parents must also be ready to handle feelings with the skill of Active Listening and send their own feelings, using good, clear I-Messages.

In one family the mother had difficulties with a thirteen-year-old daughter accustomed to getting her own way. On their first attempt to use Method 3, when it appeared to the girl that she was not getting her way, she threw a temper tantrum and ran back to her room in tears.

Instead of either consoling her or ignoring her, as she usually had done, the mother ran after her and said, "I'm really angry at you right now! Here I bring up something that is bothering me and you run away! That really feels to me like you don't give a darn about my needs. I don't like that! I think it's unfair.

"I want this problem solved now. I don't want you to lose, but I am sure not going to be the one to lose while you win. I think we can find a solution so we'll both win, but we can't for sure unless you come back to the table. Now will you join me back at the table so we can find a good solution?"

After drying her tears, the daughter came back with her mother and in an hour or so they arrived at a solution that was satisfactory to the child and the parent. Never again did the daughter run out on a problem-solving session. She stopped trying to exercise control with her anger when it was clear that her mother was through letting her control her in this way.

Most parents approach the inevitable and all-too-frequent child-child conflicts with the same win-lose orientation they use in parent-child conflicts. Parents feel they have to play the role of judge, referee, or umpire- they assume the responsibility for getting facts, determining who is right and who is wrong, and deciding what the solution should be. This orientation has some serious drawbacks and generally results in unhappy consequences for all concerned. The no-lose method is generally more effective in resolving such conflicts and much easier on parents. It also plays an important part in influencing children to become more mature, more responsible, more independent, more self-disciplined.

When parents approach child-child conflicts as judges or referees, they are making the mistake of assuming ownership of the problem. By moving in as problem-solvers, they deny children the opportunity to assume the responsibility for owning their own conflicts and to learn how to resolve them through their own efforts. This prevents their children from growing and maturing and may leave them forever dependent on some authority to resolve their conflicts for them. From the standpoint of parents, the worst effect of the win-lose approach is that their kids will continue to bring all their conflicts to the parents. Instead of solving their conflicts themselves, they run to the parent to settle their fights and their disagreements:

Such "appeals to authority" are common in most families because parents allow themselves to be sucked into their children's fights.

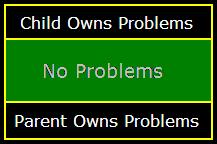

In P.E.T. it takes some convincing to get parents to accept these fights as their children's fights, and that the kids own the problem. Most fights and conflicts between children belong in the area of Problems Owned by the Child, the upper area of our diagram:

If parents can remember to locate these conflicts where they belong, then they can handle them with the appropriate methods:

Max and Brian, who are brothers, are both tugging on the toy truck, one on the front, the other on the back. Both are shouting and screaming; one is crying. Each is trying to use his power to get his way. If parents stay out of this conflict, the boys may find some way of resolving it themselves. If so, well and good; they have been given the chance to learn how to solve their problems independently. By staying out of the conflict, the parents have helped both boys grow up a little.

If the boys continue to fight and the parent feels it would be helpful to move in to facilitate their problem-solving, a door-opener or invitation is often helpful. Here is how:

MAX: I want the truck! Gimme the truck! Let go! Let go!

BRIAN: I had it first! He came in and took it away. I want it back!

PARENT: I see you really have a conflict about the truck. Do you want to come here and talk about it? I would like to help if you want to discuss it.

Sometimes, just such a door-opener brings an end to the conflict immediately. It is as if children sometimes would rather find some solution themselves rather than go through the process of working it out through discussion in the presence of a parent. They think, "Oh, it really isn't that big a deal."

Some conflicts may require a more active role on the part of the parent. In such cases, the parent can encourage problem-solving by using Active Listening and turning into a transmission belt, not a referee. It works like this:

Max: I want the truck! Gimme the truck! Let go! Let go!

PARENT: Max, you really want that truck.

BRIAN: But I had it first! He came in and took it away. I want it back!

PARENT: Brian, you feel you should have the truck because you had it first. You're mad at Max because he took it away from you. I can see you really have a conflict here. Is there any way you can see of solving this problem? Got any ideas?

BRIAN: He should let me have it.

PARENT: Max, Brian is suggesting that solution.

Max: Yeah, he would, 'cause then he'd get his way.

PARENT: Brian, Max is saying he doesn't like that solution 'cause you'd win and he'd lose.

BRIAN: Well, I'd let him play with my cars until I get through with the truck.

PARENT: Max, Brian is suggesting another solution- you can play with his cars while he plays with the truck.

Max: Do I get to play with the truck when he's through, Mom?

PARENT: Brian, Max wants to make sure you'll let him play with the truck when you're through.

BRIAN: Okay. I'll be through pretty soon.

PARENT: Max, Brian is saying that's okay with him.

Max: Okay, then.

PARENT: I guess you've both solved this problem, then, right?

Parents have reported many such successful resolutions of conflicts between children, with the parent first suggesting the no-lose method and then facilitating communication between the combatants by Active Listening. Those parents who have difficulty believing that they can involve their children in the no-lose approach need to be reminded that in the absence of adults children often resolve their conflicts with the no-lose method- at school, on the playground, in games and sports, and elsewhere. When an adult is present, and lets himself be drawn in as judge or referee, kids are inclined to use that adult- each appealing to the adult's authority to try to win at the expense of the other child.

Usually parents welcome the no-lose method for resolving child-child conflicts, because almost all have had bad experiences trying to solve their children's fights. Invariably, when a parent tries to resolve a conflict, one kid feels the parent's decision is unfair and reacts with resentment and hostility toward the parent. Sometimes parents incur the wrath of both children, perhaps by denying both children what they were fighting for ("Now neither one of you can play with the truck!")

Many parents, after they try the no-lose approach and keep responsibility with the kids for working out their own solution, tell us how terribly relieved they are to find a way of staying out of the role of judge or referee. They tell us: "It's such a relief to feel I don't have to settle their arguments. I always used to end up being the bad guy no matter how I decided."

Another predictable outcome of getting kids to resolve their own conflicts with the no-lose method is that they gradually stop bringing their fights and disagreements to their parents. They learn after awhile that going to the parent only means they are going to end up finding their own solution anyway. Consequently, they drop this old habit and start resolving their conflicts independently. Few parents can resist the appeal of this outcome.

Sticky problems are sometimes encountered in families when they come up against conflicts with kids in which both parents have a stake.

It is essential that each parent enters into no-lose problem-solving as a "free agent." They should not expect to have a "united front" or to be on the same side of every conflict, although on occasion this might happen. The essential ingredient in no-lose problem-solving is that each parent be real- each must represent accurately his or her own feelings and needs. Each parent is a separate and unique participant in conflict-resolution and should think of problem-solving as a process involving three or more separate persons, not parents aligned against children.

Some solutions under consideration during problem-solving may be acceptable to Mom and unacceptable to Dad. Sometimes Dad and his teenage son may be together on a particular issue and Mom may take an opposing point of view: Sometimes Morn may be aligned closer to her son while Dad is pushing for a different solution. Sometimes Mom and Dad will be close in their positions and the teenager's point of view is at variance with theirs. Sometimes each participant will find himself at odds with the others. Families that practice the no-lose method discover that all these combinations occur, depending on the nature of the conflict. The key to no-lose conflict-resolution is that these differences get worked through until a solution is reached that is acceptable to everyone.

In our classes we have learned from parents what types of conflicts most commonly bring out marked differences between fathers and mothers:

The point is that mothers and fathers are different, and these differences, if each parent is to be real and honest, will inevitably emerge in conflicts between parents and their children. By airing honest differences between mothers and fathers in conflict-resolution- allowing their humanness to show and be seen by their kids- parents discover that they receive from them a new kind of respect and affection. In this respect, kids are no different from adults- they, too, grow to love those who are human and they learn to distrust those who are not. They want their parents to be real, not playing a role of "parents," always voicing agreement with each other whether the agreement is real or not.

We are often asked in P.E.T. whether it is possible for one parent to resolve conflicts by the no-lose Method 3 approach while the other does not. The question comes up be cause not all parents take the course with their spouses even though we strongly urge that when there are two parents both participate.

In some cases where only one parent is committed to change to the no-lose method, perhaps a mother, she simply starts resolving all her conflicts with the kids by using the no-lose method and the father continues using Method 1 in his conflicts. This may not cause too many problems, except that the children, fully aware of the difference, often complain to the father that they no longer like his approach and wish he would solve problems the way their mother does. Some fathers respond to these complaints by enrolling in a subsequent P.E.T. class. Typical of such fathers is the one who showed up at the first session of a P.E.T. class and admitted:

Another father, at the first session of the class in which he enrolled after his wife had been in a previous class, made this comment:

Some fathers who do not learn the new skills and remain content with their Method 1 approach are often given a bad time by their wives. One wife told us that she began to build up resentments and ended up being quite hostile toward her husband because she could not stand watching him resolve conflicts with power. "I see now just how much harm to the children Method 1 produces, and I just cannot sit by and watch him hurt the kids this way," she told the class. Another said, "I can see he is ruining his relationship with the kids and that makes me feel disappointed and sad. They need their relationship with him, but it is going down the drain rapidly."

Some mothers enlist the help of class members in P.E.T. to generate the courage to confront their husbands openly and honestly. I recall one young mother who in class was helped to see how much she herself actually feared her husband and therefore had avoided confronting him with her feelings about using Method 1. Somehow, by discussing this in P.E.T., she gained enough courage to go home and tell him the feelings she had identified in class:

The effects of her confrontation astonished this mother. For the first time in their relationship, he heard her out. He told her he hadn't realized how much he had dominated both her and the children, and subsequently agreed to enroll in the next P.E.T. class in their community.

It does not always work out as favorably as in this family, when one parent continues to use Method 1. I am certain that in some families this problem never does get resolved. While we seldom hear about it, it is likely that some husbands and wives never do come together in their methods of resolving conflicts, or in some cases a parent who has been trained in P.E.T. methods may even return to her old ways under pressure of a spouse who refuses to give up using power to resolve conflicts.

We occasionally encounter a parent who accepts the validity and believes in the effectiveness of the no-lose approach, yet is not willing to give up the two win-lose approaches.

"Won't a good parent use a judicious mixture of all three methods, depending on the nature of the problem?" asked a father in one of my classes.

While understandable in view of some parents' fear of giving up all of their power over their children, this point of view is not tenable. As it is not possible "to be a little bit pregnant," it is not possible to be a little bit democratic in parent-child conflicts. In the first place, most parents who want to use a combination of all three methods really mean that they want to reserve the right to use Method 1 for the truly critical conflicts. Translated into simple language their attitude is: "On matters that are not too important to the children I will let them have a voice in the decision, but I will reserve the right to decide my way on issues that are very critical."

Our experience seeing parents try this mixed approach is that it simply does not work. Children, once given a taste of how good it feels to resolve conflicts without losing, re sent it when the parent reverts back to Method 1. Or they may lose all interest in entering into Method 3 on unimportant problems because they feel so resentful of losing on the more important problems.

A further outcome of the "judicious mixture" approach is that kids acquire a distrust of their parent when Method 3 is tried, because they have learned that when the chips are down and the parent has strong feelings on a problem, he will end up winning anyway. So, why should they enter into problem-solving? Anytime it gets to be a real conflict, they know Dad is going to use his power to win anyway.

Some parents muddle through by occasionally using Method 1 for problems where the kids do not have strong feelings-the less critical problems- but Method 3 should always be used when a conflict is critical, involving strong feelings and convictions on the part of the kids. Perhaps it is a principle in all human relationships that when one doesn't care much about the outcome of a conflict, one may be willing to give in to another's power; but when one has a real stake in the outcome one wants to make sure to have a voice in the decision-. making.

The answer to this question is, "Of course." In our classes we have encountered some parents who for various reasons cannot put Method 3 to work effectively. While we have not made a systematic study of this group, their participation in class often reveals why they are unsuccessful.

Some are too frightened to give up their power; the idea of using Method 3 threatens their long-standing values and beliefs about the necessity of authority and power in bringing up children. Often these parents have a very distorted perception of the nature of human beings. To them, human beings cannot be trusted and they are sure that removing authority will only result in their children becoming savage, selfish monsters. Most of these parents never even try to use Method 3.

Some of the unsuccessful parents have reported that their children simply refused to enter into no-lose problem-solving. Usually these have been older teenagers who already have written off their parents or who are so bitter and angry at their parents that Method 3 appears to them to give far more to their parents than they deserve. I have seen some of these youngsters in private therapy, and I must admit that I have frequently felt that the best thing for them would be to find the courage to break away from their parents, leave home, and search for new relationships that might be more satisfying. One perceptive boy, a high-school senior, came to the conclusion on his own that his mother would never change. Having become very familiar with what is taught in P.E.T. by virtue of his reading his parent's class workbook, this bright teenager shared with me these feelings:

It is apparent to all of us in the P.E.T. program that a twenty-four-hour course does not change all parents- particularly those who have practiced their ineffective methods for fifteen or more years. For some of these parents, the program fails to produce a turn-around. This is why we feel so strongly about parents learning this new philosophy of child-rearing when their children are young. As in all human relationships, some parent-child relationships can become so fractured and deteriorated that they may be beyond repair.